“Confusion is a word we have invented for an order which is not yet understood."

- Henry Miller

Editor's Note: This is part two of a beginner series on Sake Basics. Click here for part one on how sake is made.

The order of the world of sake classifications can be confusing for any new drinker to the category. “Junmai what? What’s a Honjozo or Futsu-shu? My binge-watching of Demon Slayer and Jujutsu Kaisen didn’t prepare me for any of this!” – We must have all felt this way at some point in our life.

While being bombarded by all these Japanese terms may be confusing and even feel intimidating at first, navigating through the different sake grades is actually pretty simple!

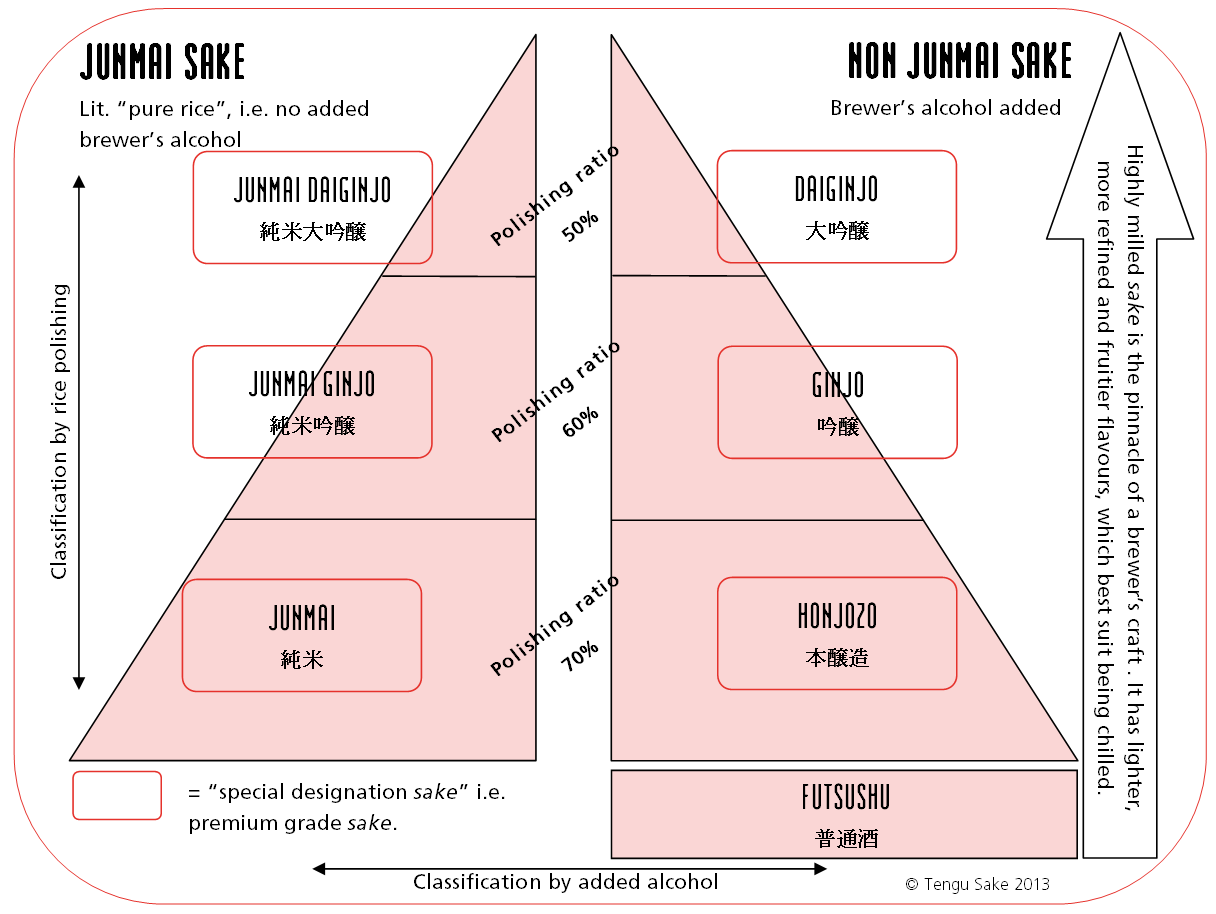

It all comes down to differences in how the sake was made; sake grades are classified based on 2 key factors:

1. The purity of the sake rice, which depends on the degree of rice polishing

This factor is what distinguishes the different sake grades. The more highly polished the rice is, the higher the sake classification.

(Image Source: hakushika.co.jp)

Sake rice undergoes polishing (also known as milling) to remove the outer layers of protein and minerals that could ruin the sake’s taste. The more polished the sake rice is, the higher the ratio of the starchy core of the rice grain in the sake, leading to a more refined, smoother sake that is able to capture more aromatic and delicious flavour profiles.

2. Whether or not “brewers alcohol” has been added in the production process (this is what distinguishes the Junmai and the non-Junmai sakes).

The distinction between the Junmai and non-Junmai sakes comes down to one thing – whether or not brewer’s alcohol (also known as jozo-alcohol) was added in when making the sake.

To be classified as a Junmai sake, the sake must be made from rice, koji, yeast, and water only. Any sake that is not classified as Junmai includes the addition of brewer’s alcohol. Some may view the addition of brewer’s alcohol with apprehension and write it off as a mere cost-saving method to increase alcohol yields. While that may be true in some cases, the reality is that brewer’s alcohol is often also added to enhance the flavour profile of a sake, improving its taste. The additional alcohol can help to bring forward the unique aromas and flavours of a sake, helping to produce a superior flavour.

Now that we’ve got those two key factors and distinctions out of the way, let’s move on to exploring the different grades of sake!

Types of Sake Classifications (Image Courtesy of TenguSake.com)

Tengu Sake has created a really helpful chart breaking down the different types of sake classifications above. As you can tell, the grade of sake are ordered according to how much the rice has been polished – the higher the rice polishing ratio, the more premium the grade of sake is. The different sake grades can then be split into their Junmai and non-Junmai counterparts.

Let’s start with exploring the different grades of non-Junmai sakes!

Futsushu Sake

At the bottom of the pyramid we have Futsushu sake, which are normal, non-premium grade sakes. Most of the sake produced in Japan (approximately 80%), are Futsushu sakes and these are the most commonly consumed types of sake. If you’ve had sake before, it’s likely that you’ve drank a Futsushu sake at least more that once because of how commonplace they are.

Compared to the other premium grade sakes, Futsushu sake has fewer quality regulations, having a higher allowance for brewer’s alcohol and no rice polishing requirements. Typically, the rice used to make Futsushu sake is polished to an average of about 70%, and the amount of brewer’s alcohol used is usually around 20% of the weight of the polished rice.

The aroma and flavour profile of Futsushu sake is most often less prominent than other specially designated premium-grade sake. However, while Futsushu sake can be understood as everything else outside of the premium-grade sake category, that doesn’t mean you can’t find a great Futsushu sake! The entry level sakes from established high-quality brands such as Dassai and Hakkaisan are also Futsushi sakes by technical categorization, and these make for a really enjoyable drinking experience too!

Honjozo Sake

Moving a grade up and into the entry level of premium-grade sake territory, we have Honjozo sake. Honjozo sakes tend to emphasis flavour, with lesser emphasis on aromas created through ageing and fermentation of the sake, which makes for wonderful food pairing.

Tsubosaka Honjozo Sake, featuring the kanji for Honjozo "本醸造酒" on the label. (Image Source: thesakecompany.com)

To qualify as a Honjozo sake, sake rice must be polished to a minimum ratio of 70% (i.e. 30% of the outer rice grain has been removed from polishing). Honjozo sake also has brewer’s alcohol added to it, making it more affordable than the other grades of premium sake.

Ginjo Sake

To qualify as a Ginjo sake, the sake rice grains need to have at least 40% of the outer layer polished off, and brewer’s alcohol may be added up to a limit of 10% of the weight of the polished rice. Fermentation is done at lower temperatures and over longer periods of time, giving Ginjo sake a lighter, fruitier taste.

Kikuizumi Ginkan Ginjo Sake, featuring the kanji for Ginjo "吟醸" on the label. (Image Source: home-work.sg)

The fruity fragrance of Ginjo sake is called ginjo-ka, and it often has a light, non-acidic taste with a smooth and “soft” texture. Ginjo sake usually pairs great with sushi and dishes that have a milder flavour due to its lighter, more aromatic flavour profile.

Daiginjo Sake

Daiginjo is a type of Ginjo sake, albeit made with even higher polished rice, whereby at least 50% of the outer grain of the rice has been polished off. Like Ginjo sake, Daiginjo sakes tend to have a fruity and floral flavour profile with a soft and smooth texture.

Since we’ve covered the ground of the non-Junmai sakes, let’s move up the grades of the Junmai grades – the sakes made with only sake rice, koji, yeast and water, with no brewer’s alcohol added. Without the addition of brewer’s alcohol, more focus is placed on the flavours of the rice and koji from the sake making process, resulting in sakes that are high in acidity and umami and less sweetness.

Junmai Sake

Among all the premium-grade sakes, Junmai sake tends to have the highest acidity and earthy umami flavours, with relatively little sweetness. While there are no minimum polishing ratio requirements for Junmai sake, it is typically polished to around at least 70%.

Junmai Gingjo Sake

Junmai Ginjo sake must be polished to a minimum of 60% to qualify as such. As Ginjo brewing techniques are incorporated into making Junmai Ginjo sake, Junmai Ginjo sake tends to have more prominent fruity and floral notes compared to Junmai sake as the acidity and umami are slightly toned down.

Junmai Daiginjo Sake

Junmai Daiginjo sakes are considered the highest grade of sake, with a minimum polishing ratio requirement of 50%. The best Junmai Daiginjo sakes are able to present a harmonized blend of refined flavour and aromas, balanced with acidity and umami.

Dassai Junmai Daiginjo 45 Sake, featuring the kanji for Junmai Daiginjo "純米大吟醸酒" on the label. (Image Source: ishopchangi.com)

The more premium the grade, the better the sake?

As human creatures, our brains are wired to seek an order and logic in most things, and the same could probably apply to our assessment of what makes a good or great sake. It might seem intuitive for us to fall back on these above sake grades as pre-defined by Japan’s Liquor Tax Act, much like how we think about getting a higher score on an exam.

But the reality is that our taste buds and personal preferences may not always be so linear. While the sake grades do indeed inform you a lot about the differences in manufacturing processes of the sake and how refined it is, is there any authority that could honestly determine what you would actually truly enjoy?

I enjoy having a proper listen to Tchaikovsky every so often, but I’d be lying if I said I’ve never gone on a 14-hour Taylor Swift binge too. Sake is very much an art form in its own ways – and our personal tastes and preferences for sake can be just as dynamic too, with variations that depend on personal preferences, occasion, food pairings, and the seasons.

So we say, it’s probably still important to understand the different sake grades. But don’t let that stop you from ever thinking “Hey, that’s a damn good Futsushu sake”!

Happy sipping!

@ChopstickPride