The world of sake and sake bottles can often be full of unfamiliar terminology. Fret not – here’s a comprehensive glossary of commonplace sake terminology that is used to describe the ingredients in sake, sake qualities, the sake production process, and to different types of sake – so you can be confident on your next sake adventure!

The Ingredients in Sake

Qualities of Sake

|

Seimai-buai (Rice polishing ratio)

|

The degree of rice polishing tells you what is the percentage that the sake rice grain has been polished down to. The lower the percentage number you see on the sake label, the higher the degree of rice polishing of the sake. For example, a rice polishing ratio of 70% means that 70% of the rice grain has been derived after polishing off 30%.

|

|

Nihonshu-do (Sake Meter Value)

|

The sake meter value is a numerical indicator of how dry or how sweet a sake is.

A (+) positive number indicates more dryness, while a (-) negative number indicates more sweetness.

|

|

San-do (Acidity) 酸度 |

San-do refers to the acidity of a sake, which is an important factor to balance out a sake’s sweetness.

|

|

Aminosan-do (Amino acid value) アミノ酸度 |

Amino acid values can tell you about how rich a sake tastes, as higher levels of amino acid causes sake to taste richer, while lower levels of amino acid causes sake to taste lighter.

|

|

Seizo nengetsu (Date produced) |

Both the production month and year should be included to indicate the sake’s date of production. |

Common Terms in Sake Production

|

Shubo (Seed mash) 酒母

|

The seed mash, or shubo, is a yeast mash produced from rice, water, and koji. The shubo is highly acidic, killing any bacteria that enters the mash.

|

|

Mormoi (Main mash) |

Moromi is the main fermentation mash, and is made from a mix of steamed rice, water, shubo, and koji. The moromi is placed in a fermentation tank, where starch from the rice is converted to sugar during the fermentation process.

The moromi is then filtered and pressed, leaving the liquid sake that we drink.

|

|

Ki-moto method 生酛

|

The ki-moto method is a traditional Japanese method to producing shubo, also known as the seed mash. Sake brewers use a paddle to manually pound and grind the sake rice, introducing lactobacilli bacteria to produce lactic acid. This manual process helps to accelerate the yeast content in the sake, which contains a lot of amino acids, giving sake a rich flavour.

|

Different Types of Sake

|

Shinshu 新酒 |

Shinshu is fresh sake that was brewed in the current year. Shinshu tends to have a fresh flavour and aroma.

|

|

Koshu 苦酒

|

Koshu typically refers to aged sake that was brewed during the previous seasons. Koshu tends to have a more mature flavour profile and smooth mouthfeel.

|

|

Chouki-shozo-shu 長期貯蔵酒 |

This refers to aged sake that has been stored for a long time. Aged and matured sake can come in various taste profiles with different qualities.

|

|

Genshu (Undiluted Sake) 原酒

|

Genshu refers to undiluted sake that has a high alcohol content and a strong flavour as water was not added to it after being pressed. Genshu can be served with an addition of warm or cold water.

|

|

Tezukuri (Hand-crafted)

|

This refers to sake that is brewed using traditional methods.

|

|

Namazake 生酒 |

Namazake is unpasteurized sake.

Sake is typically pasteurized twice before being marketed and sold – once before bottling and once after bottling. |

|

Ki-ippon 生一本 |

Ki-ippon refers to Junmai-shu that has been brewed at only one brewery.

|

|

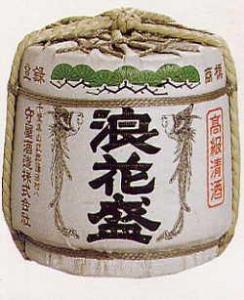

Taruzake (Cask sake) 樽酒

|

Taruzake is sake that has been stored in a cedar cask. This allows the sake to take on some of the flavours from the cedar wood, developing a unique aroma and flavour.

|

|

Hiya-oroshi 冷やおろし |

Hiya-oroshi is sake that was pasteurized once after brewing, matured until the following autumn, then bottled without pasteurization.

|

|

Nigorizake 濁り酒

|

Nigorizake is cloudy sake that is a result of coarsely filtered moromi. Nigorizake can contain cloudy and flavourful moromi sediments. It is pasteurized to preserve its quality.

|

|

Kanzake 燗酒

|

Kanzake refers to hot sake. Warming the sake also affects its flavour profile, and the alcohol in warmed sake is also more quickly absorbed by the body.

|

|

Jizake 地酒 |

Jizake refers to “local sake” that is produced by a local craft producer or artisanal microbrewery. Jizake can come in many different and exciting flavour profiles depending on the region, climate, and brewer’s method, which may not be seen as much in mass-produced sake.

|

Happy sipping!

@ChopstickPride